This article originally appeared in issue 19 of Pop Magazine and was written by Tim Fisher.

It is not a stretch to say that photographers are the backbone of the action sports industry. Not only do skate, surf and snow mags live and die on the strength of their images, none of the athletes would have profiles, and none of the brands would have exposure, without them. And none of the rest of us would have anything to put on our bedroom walls.

Having asked Steve Gourlay, Dan Himbrechts and Andrew Shield to talk about their careers in photography, we stepped back and realized that to do the guys justice, we probably need to devote a whole magazine to them. Or even a book.

Whether you recognize their names or not, these three photographers have fuelled your love of skateboarding, snowboarding and surfing, and inspired you to get out there and ride.

He’s too humble to ever say so, but Steve Gourlay is the name in Australian skate photography. Starting life as a vert skater in Adelaide, Steve went on to contribute photos to every worthwhile skate magazine in the globe, and now heads up Thomo & Coach, a Melbourne-based commercial photo agency.

As Steve is to skate, Dan Himbrechts is to snow. You know the name – for a time he was supplying every single snowboard magazine in the country (not to mention most of the advertisers) with the majority of their images. These days, Dan is based in Sydney and works as a press photographer.

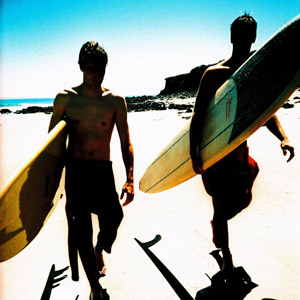

In the more crowded field of surf photography, Andrew Shield is known worldwide as one of the most well-rounded in the game. Taker of killer land shots, portraits and lineups, Shieldsy is still swimming into heavy surf with his fisheye rig, looking for new angles and finding new ways to inspire people to see the sport in a new light.

For all three, the passion for their sport came first, as Gourlay explains of his early Adelaide days. “A tight crew of us who were heavily influenced by 80’s skate mags would session drains, curbs, banks and backyard vert ramps, so I’d always take a snap of what we skated, for no other reason than it just seemed natural to do,” Steve remembers. “Looking back, I kinda regret not taking portraits of these amazing folk that taught us to skate and see life totally differently and wildly.”

Way before he took to the hills, Himbrechts was also shooting his friends skating. “Skateboarding was the action sport that really started taking the studio to the streets,” he says. “I don’t think there were many other people pushing the limit of what was possible in the film days, and back then I was reading Transworld and deconstructing every shot in the mag.

“After finishing high school I went to uni to do photography and didn’t learn anything,” Dan continues. “I learnt it all from my darkroom technician. If I see him again I’m going to shake his hand. Actually, that’s one thing I got from uni – the opportunity to spend all my spare time in the darkroom.”

Similarly, Gourlay’s interest in photography really took off when he started developing his own film around ’88. “It was somewhat of a disaster so I did a couple of black and white courses at night to get the hang of it,” he remembers. “Around this time a mate of mine (and Slam staff photog) Grantley Trenwith was taking skate and band photos and was giving me tips. He actually took me in to the city one day and made me buy a half decent film camera,” Gourlay says. “I struggled for a while with transparency film until one day I shot a roll, got my results back and it all started to make sense. As a vert skater back then, ironically my first published shot that GT thought worthy was a street photo. It ended up running in Slam and I was so happy.”

Unlike Gourlay and Himbrechts, Andrew Shield tried to keep his surfing and his photography separate. “I used to think that surf photography would just get in the way of surfing,” he says. “For two years, I was shooting cricket, footy and other mainstream sport for a photo agency. I did a two month stint through Indonesia shooting lineups and photos of my mates with a diving housing, and decided to send about 200 shots to Australia’s Surfing Life (ASL). Lee Pegus, the photo editor, invited me in. He and editor Tim Baker both congratulated me on the photos, and I remember Bakes said it was great to see photos of people doing Indo overland rather than a boat trip. They ended up using one shot from the trip! Over the years I had a lot of great feedback and advice from Lee Pegus. He used to constantly remind me that you can’t make a living from surf photography.”

Interestingly, none of these three photographers ever considered they could make a career from what they were doing. They just did it because they loved their sport, and wanted to stay connected to it by any means possible.

“I finished year 12 in ’91, and between the time I finished school and uni I tried snowboarding,” says Himbrechts. “If you were around back then, you might remember the last couple of pages in a few skate mags had some photos of snowboarding, usually a guy wearing fluro looking awkward in the air. But it looked kinda cool, and for a skater, kind of easy, you know? So me and some mates decided to try it out. I grew up in the western suburbs of Sydney and it was not a thing that anyone I knew did. I didn’t know anyone who did snow trips. Nobody. The whole snow thing is so pricey, but it’s like anything: once you become addicted, by any means you’ll get there. I got really pumped on snowboarding, saved up a bunch of money and did my first trip overseas to Whistler in ’96. I came back and started working in construction so I could get more money just to get back over there. I had finished uni broke like everyone else, and I wasn’t seeing photography as a career. I had wanted to be a press photographer when I finished school, which would have meant a cadetship or being a copy kid, which were highly coveted roles back then.”

It’s Gourlay who sums up the organic move into full time photography. “It never crossed my mind that ‘this is a career move I need to make’,” he says. “I was just skateboarding with my mates. Man, honestly, it just evolved one step at a time, making the odd fuck-up here and there but also the odd decision that I felt in my heart was right. Animal Chin exists, you know.”

It wasn’t until his early 30s that Andrew Shield’s photography took priority over actually going surfing. “I’d been surfing every day since I was 17 and it didn’t seem like too big a deal at the time to be doing something that cut into my surfing time,” he explains. “Although surf photography is a pretty crap deal for surfers – you would honestly get more surfing done with a 9 to 5 job. For about the first 10 years of my career I used to shoot every single day the sun was out and I could find someone worthy to shoot, which isn’t hard on the Gold Coast. It can get a bit tiring if you’re swimming for a few hours trying to get water shots, so you don’t really feel like going surfing as well.”

“I don’t ever lose the passion, but sometimes I do find it hard to get motivated to go skate,” Gourlay agrees. “What really inspires me is seeing my mates’ love for skating. They often – well, try to – make me go skate and leave my camera behind. Photographically, I don’t loose the passion either, it’s more about finding more creative energy after a long week of shooting. Never once have I found this bad a thing, it’s just down to planning my time so I know when I can throw a camera over my shoulder and get amongst the rad shit.”

All the time he’d been saving and snowboarding, Dan Himbrechts had kept shooting. “I always thought I had a good eye, but in 2000 I still hadn’t made anything of it, and this is five years after finishing uni. I’d just been living,” he says. “Canada was the turning point. “I met a young Australian kid there named Nick Gregory, and when I went back the following season he was there again. He said a magazine in Australia wanted to do a piece on him, and would I be interested in taking some shots? So I bought two rolls of Provia slide film, shot them off, sent them to Mouse (Luke Burchett), and he sent me an email back saying he liked the pics. I thought, ‘hold on a minute, does that mean they’re actually going to use one?’ They ran a sequence and another photo so I kept sending them stuff, and by this stage I was thinking this would be the fucken perfect job, but I knew if I wanted it to work I needed better gear. For the next few years I worked my arse off in every shitty job, collecting equipment in dribs and drabs, buying a flash here, a new lens there. It probably took five years to get my ideal kit together, and in that time I was working as a housepainter six days a week but getting regularly published. I was sent on my first editorial trip in 2003 for Snowboarder, then every year after that I was doing more and more. It was brilliant. I loved every minute of it. But I didn’t make a cent, and in some ways I’m still paying it off.”

“In my early twenties I was on the dole and I remember times when I was really poor,” say Gourlay of his own early days. “Out of necessity and stupidity I would grab film and batteries to get by to shoot a photo so I could just pay rent and eat tuna and noodles. I wasn’t shooting anything else – I had such a crazy one-eyed view on the world that skateboarding was the only thing that was important in life. It wasn’t until about ‘95 that I realised I wanted to actually learn the craft of photography, so I studied commercial photography in Adelaide. Back then I would be out every day, rain or shine and a few nights a week with generators and lights, basically 24-7. It was such amazing fun to be able to do this full time. It was bloody exciting times to be asked to take off travelling with a bunch of talented skaters to go shoot and have a shred around the world when the opportunity arose. Very lucky times. It was what’s kinda referred to as the ‘golden years’ of the industry. It’s cheesy, but it’s true.”

Around the same time, Andrew Shield’s career was beginning to take off. “In ’98 I did three overseas trips for ASL. One of them was to the Maldives with an 18-year-old Mick Fanning and Joel Parkinson. I made some decent money from the trip and got a real taste for it. I used to think I would struggle to make enough money from it for it to be a viable career. I’ve been so blessed to have the support of ASL magazine for the last 13 years.”

While the surf industry had established and profitable magazines and brands that were able to invest in regular photo trips, things were, and still are, very different for the smaller Australian snowboard scene. With its limited season and the prohibitive costs involved with getting into the sport, it wasn’t surprising that the industry tried to put the squeeze on photographers.

“The $200 photo was a killer for the snowboard industry,” Dan Himbrechts explains. “Somewhere along the line, someone – a retailer – came up with a figure that you could pay $200 to use a photo in an ad. This made it doubly tough just trying to get any decent return on what you’d tried to create. I never sold a photo for $200, I had a walkaway price. It didn’t matter if I hadn’t sold a photo for a month and I was eating noodles, I’d give them a price, and if they said ‘Well, so-and-so will sell me one for $250’ I’d say, ‘well buy that then’. It never works. You might think it’s your big break, but if you sell a photo for $200, five years later, you’ll still be the $200 guy.

“There’s a whole generation of guys shooting now who must be content with the $40 they get from having a photo run on the web,” says Andrew Shield, of the equivalent problem in surf photography. “I feel sorry for them because it’s not going to lead anywhere. The forecasting websites aren’t going to fund trips; they’re happy to take submissions from whoever is in the right spot at the time. These new guys seem happy with the pocket change and the photo credit and the chance to post on Facebook that they got photo of the day. I feel like shaking them and telling them they’re being taken advantage of! I can still see shots of mine in a magazine from a few years ago, but who looks back at web archives? It’s up for a day then vanishes forever.”

Which brings us to digital. The shift from film was so seismic, and affected so many different aspects of the media, it’s hard to believe it’s only been five years since digital photography was widely embraced.

So what were the immediate changes that digital brought to the industry back in 05-06? “My initial view was that the results weren’t up to anywhere near film quality,” says Gourlay. “Most guys hadn’t got their heads around the fact a digital image requires post-production, so some images looked terrible. What made me change was that you could shoot sequences for only the cost of a computer. As a skate photog this was good news as tech skating was progressing rapidly, so instantly we could stop burning 20-30 rolls of film per trick [it wasn’t unheard of to shoot 40 rolls of film a week]. So while the quality wasn’t there yet, we were hyped, and the mags and companies were stoked as their huge film budgets where now zilcho. Also, if you travelled OS, there was no more taking a massive bag dedicated to just your film and having to deal with x-ray dramas going thru security.”

“The thing that’s really important to note is that the flagship Canon and Nikon cameras cost the same back then as they do now,” says Dan. “But the difference is, back then they lasted. Once film cameras got to a certain point – Nikon F5, Canon EOS1V, 1N – there was nothing more you could do with a film body. I bought my first good camera in 2002, a Nikon F5. I remember having it on the front seat of my Subaru that I’d had for eight years and thinking fuck, this little black box is worth more than my car. And my car is the most reliable thing I’ve ever owned. That camera was superceded eventually but if it wasn’t for digital, I’d still be using it – it’s a beautiful camera.

“But from 2006 to now, which is a relatively short time, I’ve had to upgrade to five different professional digital bodies.”

While upgrading professional digital cameras every year or two is a huge expense, there are a lot of positives to digital for the average punter.

“Digital has been great for getting people stoked on photography,” says Dan. “Everything used to take a long time to learn; you shoot a roll, take it to the lab, get it back, and usually it’ll take a week. When you look at the photos that work, often you can’t remember what you did to make it work. It took a long time to learn the craft, how to see and read light, work out how it would play on film.

“Now, you shoot a photo and look at the back of your camera. If it’s too bright, you can turn a knob to make it less bright. Someone might not know about composition or anything else but they can take a good picture, and that’s great,” Dan continues.

“But the… Worst… Thing about digital, is that every man and his dog can take a photo on a digital camera and think they’re Ansel Adams. The exposure’s not there, the depth of field’s all wrong and it’s simply because they haven’t learnt the fundamentals of photography. They’ve just picked up a camera and made it work because of what they see on the back of their screen.

“I would get emails all the time from kids wanting to get into photography,” Dan continues. “I would always tell them to shoot lots of photos, look at what was getting run in the magazines, look at the quality that makes a great action sports photo. Keep shooting photos, then when your shots start looking like they do in the magazine, do a tight edit of five, and show them to someone.”

Advice that’s as true now as it ever was.

Just remember why you’re doing it, how small the financial returns are, and how much work you’ll have to put in. But in saying this, we know that if you’re keen, you’ll do it anyway. Like Shieldsy says, “I’ve sacrificed a lot of surfing time and worked really hard. But even when I was doing 60 hours per week for years, it never felt like work.”

“Yes, we are underpaid if you compare us to most other areas of photography,” says Gourlay. “What we have though, are the skills to shoot anything as we’ve had to deal with the shittiest spots you can think of. We had to learn how to light some crazy conditions, and do it fast. Unfortunately, it’s a small industry so our payments will always be relative unless a bloody miracle happens. C’mon miracle …”

Check out more of the guys work stevegourlayphoto.com, danhimbrechts.com, andrewshield.com.au